Author:

Stewart Berry

7 December 2015

Updated 12

August 2025

Every ten years, in a process that profoundly impacts American politics, the legislative districts are redrawn to determine who votes where. But because of a practice called gerrymandering "we, the people" are not necessarily deciding who represents us.

The United States Constitution requires that a population count, the decennial Census, serve as the basis for redistricting. Congressional districts are then reapportioned among the states and each state is divided into districts of equal population. State legislatures and many local governments work the same way. Since the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the redrawing of state and congressional lines must also maximize any clear opportunity for minorities to elect candidates of their choosing.

In all but 13 states, legislators redraw state and congressional districts. As you can imagine, the highly charged and competitive political environment has resulted in less than ideal boundary changes, even when legislators obey the letter of the law.

And if the outcome of a lawmaker's next election is effectively pre-determined by how they draw a map (the process known as gerrymandering), then they are less likely to listen to voters. If a lawmaker is corrupt or failing on their campaign promises, voters have less power to hold them accountable and minority neighborhoods may have their voting power diluted.

The minority vote protections in the Voting Rights Act resulted in a situation where the party that elected minorities also controlled the House of Representatives*. Democrats championed the process, redrawing districts to maintain minority populations*. Due to this, Democrats largely controlled Congress for 40 years, from 1955 to 1995. Now this "clumping" is hurting Democrats. Democrats are increasingly winning the majority of the votes in small geographic, mostly urban, areas. These urban districts are very hard to gerrymander*. This is because most local governments want House districts that respect local boundaries and that local politicians can defend in the polls, while Democratic city governments can influence Democratic state legislators who might otherwise be tempted to gerrymander.

GOP drawn boundaries have been seen to overcrowd districts created by Democrats with disproportionate amounts of minority populations. By increasing numbers in a safe Democratic district, Republicans reduce the influence of the liberal voting bloc in both state politics and congressional elections. Republicans controlled the US House from 1995 until 2006.

However, the Republican party retained its power in state legislatures following the losses by the Democrats in the 2010 mid-terms. The Democrats were unpopular with voters at this time, allowing Republicans to implement a political effort called REDMAP that enabled them to redrew favorable maps with the 2010 Census data.

What is the cause of this situation? The lack of impartial redistricters or tools that make it too easy to redistrict?

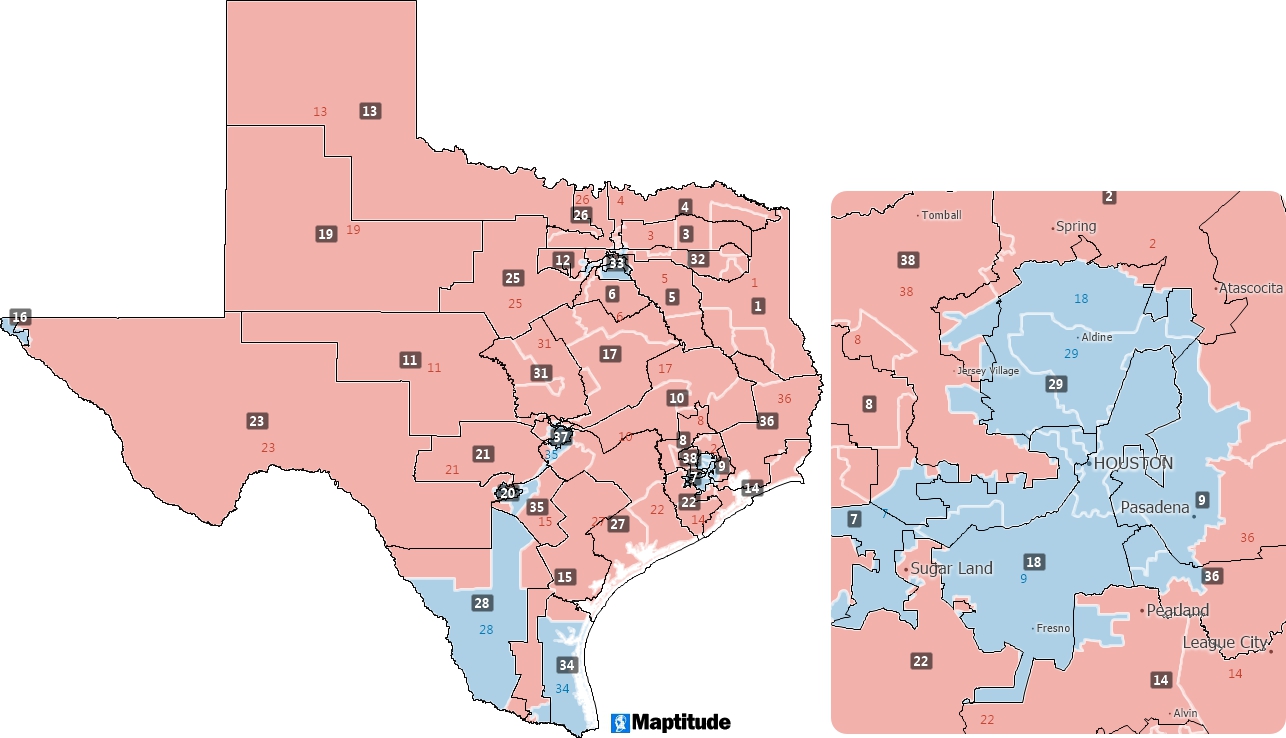

The widespread use of redistricting software has made the drawing of redistricting plans easier from a technical perspective. But the software is simply a tool and when put in the wrong hands can be used outside of the original intent of the application. Maptitude mapping software is the dominant product used to redistrict (www.redistricting.com), and is regularly mentioned in the mainstream press and has been covered in Rolling Stone, Dallas Morning News, Boston Globe, The Atlantic, The Atlantic Cities, The New York Times, and many other media outlets. However, it is often a reference in regards to how Republicans use Maptitude to redistrict. This is despite Maptitude being used by a supermajority of the state legislatures, political parties, and public interest groups of both political parties.

So is it the redistricters fault? Several states already use independent, nonpartisan redistricting commissions, and are having great success. In 2011 for example, California established a citizens redistricting commission that used Maptitude to successfully redraw the maps. In another example, in Oakland, anyone could propose a district map by using Maptitude.

In the rest of the world, systems like California's are closer to the norm. Indeed, in Canada, Australia, and many other Western countries, politicians aren't allowed anywhere near the district maps. But politics can still impact redistricting. In Saskatoon, Canada, the 2002 independent boundary commission had wanted to change the rural-urban boundaries into urban districts to better represent the character of the areas. But this was opposed by the party that would lose seats, and the proposed changes had to wait until 2012.

In the UK, changes to the boundaries and number of constituencies are being proposed to save money and because the average size of the electorate in a Labour party seat is 68,487 compared to 72,418 in Conservative party seats and 69,440 in Liberal Democrat party seats. The UK does not have a history of legal challenges to redistricting plans, and these challenges may cause judicial review of specific boundary commission decisions as well as to variations in the overall national redistricting plan. While the Electoral Commission has been effective in creating equal seats, the process has introduced biased redistricting that has gone unchallenged. Availability of US-style redistricting software (of which Maptitude is the best-of-breed) will enable serious partisan and non-partisan (interest group, local group, etc.) opposition to be mounted, while enabling boundary commissions to objectively defend new delineations.

Should people be involved in the process at all? While there have been attempts to completely automate the creation of districts using non-partisan computer algorithms, it has been argued that with only a small handful of variables the redistricting problem becomes incredibly complex very quickly, so complex that it is "probably impossible to create a computer program that [automatically] solves these problems optimally and reliably except in very small or limited cases."

Human intervention in the process is currently the best way to redistrict, and Maptitude supports the production of defensible, reproducible, and consistent plans, based on a rigorous software implementation that adheres to the standards and data required by the plan creation process.

Maptitude cannot prevent intentional biases that may be introduced into plans, but does enable serious non-partisan opposition to be mounted to proposed districts, while enabling redistricting bodies to robustly defend new delineations. Simply put, a fully transparent and open process is required to produce boundaries worthy of a democratic process.

For decades, partisan bias in the House has swung both ways, with Democrats enjoying a built-in edge through much of the late 20th century, and Republicans gaining a structural advantage in the 2000s and 2010s. Now, for the first time in over twenty years, the efficiency gap (the difference in "wasted" votes between parties) is virtually zero*. In fact, Democrats currently have a slight edge in wasted votes, tipping the efficiency gap modestly in their favor. In the 2022 and 2024 cycles, Republicans squeaked out narrow wins, not through rigged lines, but because they captured just enough of the vote.

What brought this change? Both parties drew partisan maps when they had the opportunity. Some long-standing Republican-leaning maps have been replaced or reworked, while Democratic-leaning maps in states like Illinois and New York have been reinforced or expanded. Also playing a role are redistricting commissions, which can reduce partisan bias but do not ensure fair outcomes in every case, and shifting political geography, with Republicans gaining in cities and Democrats holding firm in suburbs.

But don't mistake this momentary balance for lasting reform. Many states still use the map-drawing process to tilt the field, and the next redistricting cycle (whether mid-decade tweaks or the post-2030 Census overhaul) could hand the advantage to either party. The map itself isn't the problem; it's how the lines are drawn. Despite tools such as Maptitude including every measure and capability to ensure fairness*, the real issue lies in the political process, not the software. Until redistricting is done through fair, transparent, and accountable methods, any appearance of balance is just temporary.

Every great detective needs solid evidence, not just assumptions. In the redistricting "murder mystery," AI ensembles aren't sketching the culprit; they're generating thousands of alternate versions of the crime scene.

The Maptitude AI Ensembles use a proprietary version of the ReCom method, which employs a Markov Chain Monte Carlo algorithm to randomly generate thousands of district maps. Each one varies slightly, based on constraints like equal population, compactness, or county splits. These maps form a "bell curve" of possible plans. If the proposed plan stands out drastically compared to the ensemble, that suggests it's less a natural outcome and more a crafted one.***

It's not about AI picking a map for you. It's about revealing which maps are plausible democratic options, and which ones stick out like a red herring. Users, whether commissions, watchdogs, or reform advocates, get real, data-backed comparables. When one plan is a statistical outlier, that's hard evidence that something suspicious might be going on.

The technology is impartial. The process is not. Tools like Maptitude make it possible for anyone, from reform advocates to state officials, to scrutinize and compare maps using the same data-driven methods that professionals rely on. That's how you build trust in the evidence and keep the investigation honest.

Learn more about Maptitude for Redistricting

Schedule a Free Personalized Demo

Home | Products | Contact | Secure Store